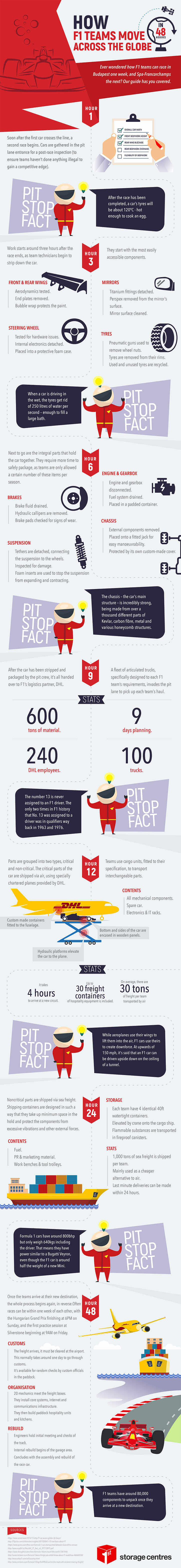

How the Formula One fleet moves on the earth (infographic)

There is an old saying in the Military Academy: "Amateurs consider tactics, and professionals consider logistics." I have been participating in competitions all my life. In general, the Grand Prix is the most important to me. I have seen how these teams have become bigger over time; and how the game has become more distant. Therefore, I know that, to some extent, moving all people and materials from one track to the next is a real hassle. A clever infographic recently provided by our friends at Storage Centers in the UK helped us understand how this happened.

It’s a logistical nightmare for any given Formula 1 team to contemplate, let alone envisage on a week in, week out basis. Now realize there are ten F1 teams. It’s like coordinating the Normandy landings every couple of weeks. This is how they do it.

Packing Frenzy

Going For The Nuts & Bolts

Big Budgets & Grenade Engines

Careful Movements

Logistics & Assembly

Careful & Delicate Process

Packing Frenzy

For simplicity’s sake, let’s just say we’re looking at this from the end of any given race. All the cars finished, there were no accidents, and nothing was destroyed.

First, the teams start to pack up everything except the cars. The cars are kept in parc ferme conditions, that is, impounded, so they can pass through tech inspection to make sure no one cheated (no lightweight cars or something goofy like hydrazine in the fuel). While the cars are checked by the race stewards, everything else is packed up, most of it into these totally cool, anvil-like flight cases you see rock bands use on tour. Jacks, laptops, alignment plates, crew helmets, the lot. And spares, spares, spares (racing teams carry spare everything)!

By the time the cars roll out of parc ferme about three hours later, most, if not all of the accouterments are ready to move.

Going For The Nuts & Bolts

They start unbolting everything – okay, most things – into smaller, more easily-wrapped and transported bits and pieces. So, the front and rear wings, for instance, get pulled and inspected for any race-related damage or fatigue issues; then swathed in bubble wrap to protect their delicate aero surfaces. The mirrors are pulled as are the wheels and tires. Tires are given back to Pirelli, checked for flaws, wear damage, and the like, then recycled or, in some cases, sold after the season to collectors. I actually had a pair of Damon Hill’s tires from the Canadian GP for many years, they made a great coffee table base.

The steering wheel is pulled, checked, then placed in its own flight case. I know that seems excessive, but a modern F1 steering wheel runs you around $55,000. You don’t want to screw it up.

As the car gets broken down further, you see what’s known as integral parts. That’s another way of saying “very important and expensive” parts. It’s also a way of saying the stuff the FIA (the sport’s governing body) watches closely. This includes the brakes, suspension, engine and gearbox, and finally, the chassis itself.

Photo: Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile.

Big Budgets & Grenade Engines

As a way to keep costs down, the FIA limits the number of engines and gearboxes a team can use during the year. I know, it seems kind of silly. How many engines can a team go through anyway. The answer is as many as they can buy. And since F1 teams have suitcases full of money, you’d be amazed at what they will spend it on, given the chance. Even a small team these days has a yearly budget in the hundreds of millions of dollars. You can imagine what Ferrari or Mercedes-Benz or McLaren spend.

Before rules like this were put in place, teams were known to run special “qualifying engines” for that extra little advantage. They were called “grenade engines” because they were good for three, maybe four laps at full song before blowing up like, well, a grenade. They cost $250,000 each. So what? We’ve got a budget of two million dollars a day (that’s no exaggeration), so who cares? Put another one in, let’s make another run for the pole.

Before the FIA cracked down on this, there was talk of some teams making entire cars just for qualifying. Cars that were right on the edge of what the composite tubs and structures could withstand. They would only survive for around 10 laps max before they were thrown away. Multiply that by the number of drivers on the grid (in today’s case, that would be 20) and you can see where operating costs would grow so high even NASA would shake their head.

Photo: Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile.

Careful Movements

The brakes are completely disassembled and inspected. The pads and discs are checked and analyzed for wear and stress before being junked. (They last for one race and cost about $100,000 per corner: x 4 corners, x 2 cars per team, x 10 teams, x 20 races = The GDP of Burundi). All fluids are drained, checked for particulate, then recycled. The suspension – A-arms, bell crank bits, wheel tethers that hold the wheel/tires to the car in the event of an accident – are completely taken down to their individual components. Foam spacers are inserted into the A-arms to prevent them from expanding and contracting while being flown to the next race.

Everything is inspected. If it’s damaged, it’s junked.

Material engineers (and top teams have more than one, I assure you) want to keep the usage cycles to a minimum. The engine and gearbox are separated, drained of all the oil, fluid, and gunk. They are inspected for signs of wear leading to possible failure; put under FIA seal, and loaded into their individual flight cases. The chassis, although not taken down to the bear tub, is pretty well stripped; then wrapped in its own, custom-tailored Lycra cover for protection. Carbon fiber, although very strong, is susceptible to puncture damage, so an inattentive swing of a mechanic’s arm with a screwdriver can trash the whole thing.

Photo: Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile.

Logistics & Assembly

Once everything is disassembled, packed, and crated, the teams turn their stuff over to DHL, F1’s logistics partner. For DHL, this requires transporting 600 tons of materiel, nine days worth of planning, 240 employees, and 100 trucks just to move the stuff to the airport.

Once at the airfield, the parts are loaded onto different planes. One plane gets the critical parts: the car itself, engines, gearboxes, IT rack-mounted gear, electronics, things along those lines. Some of the non-critical parts are loaded onto those cargo modules you sometimes see at airports. They use 30 freight containers that amount to, on average, about 30 tons of stuff per team. Remember, there are 10 teams.

The non-critical stuff – fuel, marketing swag, work benches, tool carts etc. – gets shipped in 40-foot containers, four per team via sea routes or over-the-road. This is around 1,000 tons of stuff per team. If a team needs something fast, DHL can overnight it directly to the pit garages, anywhere in the world.

Careful & Delicate Process

Once teams show up at the new track, it is, as the U.S. Army would put it: “assembly is the reverse of disassembly.” Up to 40 mechanics per team are there just to see stuff unloaded and put in its proper place, while other mechanics start bolting stuff back together. All the while, car parts and components are checked, checked, checked, and checked again. The last thing a team wants is for a “bad” piece – something beyond its useful life or something damaged – to make it onto a car and break, possibly costing the team a win or injuring the driver.

See? Easy-peasy-lemon-squeezy! The handy graphic below from Storage Centres explains more.

Tony Borroz has spent his entire life racing antique and sports cars. He is the author of

Bricks & Bones: The Endearing Legacy and Nitty-Gritty Phenomenon of The Indy 500, available in paperback or Kindle format.

Follow his work on Twitter: @TonyBorroz.

How the F1 team crossed the earth within 48 hours of the storage center.

-

Latest

Balance and control: Brembo prepares for the 2019 Formula One Championship

Balance and control: Brembo prepares for the 2019 Formula One ChampionshipBrake is an interesting thing. If you think about it, cars, especially high-performance cars, are going to drive, not stop. But brakes can actually help you walk faster; they are not just to slow you...

-

Next

Summer 2011 Family Road Tourer

Summer 2011 Family Road TourerIn the 1950s when the main road network in North America was formed, a phenomenon occurred when family car trips in the summer began. It was initially determined to be the time when the large station...

Popular Articles

- The Canadian government invests in the first Canadian-made electric car

- Stellantis strengthens electrification

- 2022 Ford Maverick debuts

- The Canadian government requires 100% of Canadian car and bus sales to achieve zero emissions by 2035

- Extend electric car rebates to businesses and non-profit organizations BC

- New general manager of ADESA offices in the U.S. and Canada